This was my keynote talk for the 7th Annual Native American Alumni Dinner on April 7, 2017 at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion.

Hau Mitakuyapi. Nape Cuzayapi. Cante Waste.

What an honor and privilege it is to be invited back to the homelands and to my alma mater, the University of South Dakota. Wopila to the USD Tiospaye Council and the USD Alumni Association. I also want to give a special shout out to Sydney Schad, a former GEARUP student of mine, for all the hard work in getting me back home. A lot of my former GEARUP students, colleagues, mentors, and relatives are here tonight, and I wish you all well. Wopila.

This is the second time I’ve been invited back to USD since I left in 2010. Returning home is always bittersweet. I’m always anxious to visit friends and relatives. Equally so, I’m troubled by what exactly I’m returning to. What has changed? Who has changed? Did I change? What is changing? Are we going forwards or backwards?

The last couple of months appear like we are moving backwards in time. Some would have it that we should “make America great again.” And it makes me think: when was America ever great? Back in the sixteenth century Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian explorer, got lost somewhere at the delta of the Amazon river. Native people took care of him and his crew. He was the first to recognize these continents were not Asia — even Columbus still believed he had landed in Asia. As a result, an entire hemisphere took his name: America.

In 1516 an Englishman Sir Thomas More would later take Vespucci’s writings on the egalitarian Indigenous societies he encountered and write the book and coin the phrase Utopia. Utopia is a Latin-derived word that literally means “nowhere.” More’s ideas of an egalitarian society were also shaped by Europe’s bloody civil war, also known as the Reformation. The losers of that war, the Protestants, banished from their lands, would seek refuge in the “New World” and attempt to make society anew — or, as some saw it, “make heaven on earth.”

These were the early seeds for the greatest empire in the history of the world that would eventually call itself the United States of America. “America” may have been a “nowhere” place for Europeans. But it was a somewhere place for the countless nations of people who lived here.

There was also major problem: the empire needed land. And the “New World” was actually an Old World fully inhabited by people with their own knowledges, their own histories, their own civilizations, and their own ways of knowing the world. Those ways of knowing didn’t carve the world up into owners, workers, races, and the “civilized” and “uncivilized.”

So what “America” — what utopia — are we exactly returning to?

Don’t take my word for it. I’m a pessimist and a guarded skeptic when it comes to history and change. Pessimism allows us to be cautiously optimistic that things can and will go wrong. When they go right, we’re pleasantly surprised. As a student of history, I don’t think the founding of “America” was ever morally right. And I’m equally hesitant to call myself an “American” or the United States “America” after a lost Italian explorer.

American history feels like the movie Groundhog’s Day. Have you seen that movie? We wake up knowing today will be the same day as yesterday. Like Bill Murray, we have mapped out the entire day — armed with the previous knowledge of how the day will repeat itself. We can change it and modify it to certain degrees, hoping for better outcomes and build on past mistakes. We can take the groundhog hostage. We can coerce and trick people and bend them to our will. But, in the end, we will still wake up on Groundhog’s Day. Will we find that ultimate purpose or will to break the cycle? Will today be the day we finally fall in love with the lovely Andie Macdowell so we can break the cycle and wake up tomorrow to a new day? Maybe. But most likely not. At least, not yet.

Yesterday, when some of us may have forgotten the US was still at war in Afghanistan and Iraq, we woke up to the news that the US has now bombed Syrian military bases. We will wake up tomorrow and the US will still be at war in all three of those countries. Maybe we should ask Bill Murray from Groundhog’s Day if he remembers why we’re still at war. Because some of us seem to have forgotten. As educators, we are, and will be, teaching generations of students whose entire lives have only known war. I’m not just talking about “American” students whose country has been at war for the last fifteen years. I’m also talking about the students from the countries the US bombs, invades, and puts military bases. At the very least, we have an obligation to give them a home if the US military blows up, invades, or occupy theirs.

Is this what we want to leave for our future generations? No waking up for tomorrow, just waking up for more war today?

The last time I left my homelands was on November 8, the day Trump was elected. I also started smoking cigarettes again that day. Today, I returned home the day after Trump bombed Syria. This is what it means to return home for me.

To have a tomorrow and to wake up from today, we need bigger collective imaginations, more courageous collective dreams, and more intimate knowledges of who we are not just as individuals and not as “Americans” but as people, human beings. And we need to intimately know this land before it was ever called “America.” There is a name for it other than “America.” Some call it Makoce — the earth, which is as much alive as our histories. Its beating heart is He Sapa, the Black Hills, and its aorta is Mni Sose, the Missouri River. What do to the earth’s heart and what we put in her veins, we also do to ourselves.

The important thing, however, is that we can learn from history and remember we carry with us — each of us — the past experiences of ancestors — their misdeeds and their victories. We must also learn from the land. Even if you’re like me living in a tangled, concrete maze thousands of miles away, we must remember it was here that the first Lakotas and Dakotas became human — where we emerged from the wase, the red earth, to become the Oyate Luta or, as they say on this side of the river, the Oyate Duta, the Red Nation. This is where the town Vermillion takes its name from the Wase Wakpa, the red clay creek. When we emerged, we were pitiful creatures, the ikce wicasa, the common people, who depended on our relatives the Pte Oyate, the buffalo nation, and the Mni Oyate, the water nation, to give us life. Hence the phrase, Mni Wiconi, water is life. They protected us and cared for us. And we must ask, where are those nations today, our relatives who helped us realize our own humanity? How are we protecting them and taking care of them today?

I was born and raised along the banks of the Mni Sose, the Missouri River. I believe it was during a blizzard. I was too young to remember! The town was Chamberlain, the white-dominated border town just twenty miles south of Crow Creek.

From what I’m told, my ancestor from my father’s side Melissa DuFonde, a Dakota woman, was orphaned during the 1862 US-Dakota War. Her Dakota name was Mni Oke Win, the Woman Who Digs by the Water. As a young woman, she fled to the Yankton Agency, where she was shipped upriver north to Crow Creek. Crow Creek was a concentration camp for the survivors of the war, mostly old men, women, and children who were banished from the homelands, Mni Sota, and Minnesota Territory. Because her family was killed off either by soldiers or vigilante settlers — we don’t know which, we don’t know our connection to the Dakota people or the Dakota Makoce. But it doesn’t matter, because she was taken in as a relative and later married into the Kul Wicasa Oyate, the Lower Brule. Through kinship she and her descendants (such as myself) became Lakotas. It was during those apocalyptic moments, when entire families and nations were being exterminated and actively hunted, that we cared for each other by making new relatives.

I am also told Chamberlain was once called Maka Tipi — or cave dwellers. The name has two meanings. The first comes from when our Dakota relatives fled the US military’s “columns of vengeance” and took refuge in the Missouri River cliffs at the river crossing now called Chamberlain. In 1863, generals Sully and Sibley led punitive campaigns against fleeing Dakotas from Minnesota Territory, culminating in the massacre 300 women and children at Whitestone Hill in what is today North Dakota. The second meaning comes from the first white people who attempted settle the area. Unfamiliar with the weather and the terrain, their flimsy structures were quickly torn apart by summer thunderstorms. At the turn of the nineteenth century, headmen from Lower Brule and Crow Creek came to Chamberlain and helped the settlers construct the first Masonic Lodge. It was one of the first stone buildings and the first building on main street, most likely in hopes of establishing friendly relationships with their white neighbors who had, several generations earlier, hunted fugitive Dakotas for scalps. Those early attempts at making relatives with settlers, literally cemented in the stone buildings, were genuine and sincere for our part. Yet, Chamberlain, although it’s population is slowly becoming more and more Native, still to this day refuses to allow Lakota and Dakota honor songs at its high school graduation. Perhaps they have forgotten how pitiful they were when they first arrived to this land. Perhaps they have forgotten their ancestor’s pledge to live in peace here. Perhaps they have forgotten their own history. Perhaps they truly believe they are in the nowhere place called “America,” where promises and history don’t matter.

****

I blame my bad eyesight on my mother, Angela Quinn-Estes. She was an educator and taught me to read before I ever attended school. Poor people move a lot. I didn’t understand that at first. But I once counted we had moved over twenty-three times before I turned eighteen. As a child, we bounced around from Mitchell, Gregory, Winner, Brookings, and finally settling back in Chamberlain. Everywhere we went, I had books because we had libraries. I was consumed with books and information. I stayed up late reading everything I could get my hands on: comic books, novels, newspapers, the ingredients for toothpaste, etc.

My mother’s ancestors were poor Irish Catholic settlers from Faith, bordering the Cheyenne River reservation. Her father became an orthodontist and she was raised most of her life in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina. From what she tells, they were kind people to their own but also were deep-seated racists. Maybe that’s why we never knew that side of the family very well. Us half-breeds tainted the lineage. She met my father, Ben Estes, in Chamberlain along the river. My father has a thick rez accent and my mom, until the day she died, kept her southern drawl. So I inherited from my parents a peculiar accent, bad eyesight, and the tendency to read tubes of toothpaste.

If my mother gave me education, my father gave me compassion. I would later learn from my father the long, deep history of the land. You may not know it, most likely because his occupation requires him to see people when they are at the worst (he’s a cop), but dad loves his people and the land. My brothers and my dad all work in jobs where if they visit you, it’s probably on the worst day of your life. They are public servants, who respond to fires, accidents, violence, etc. I don’t envy them. Meanwhile, I just read books and write what I think are witty and clever things. Dad is what I would later learn descended from a long line of Lakota nationalists — patriots who love their land and people. That’s where his compassion comes from.

In my short life, those two things are what kept me alive: compassion and knowledge. They are also things that can never be taken from you. They may take your land and you may be poor as hell, but they can never take away your knowledge and compassion. That’s who I am, or at what I aspire to be: a compassionate, educated, Lakota, with Irish settler ancestry that I know nothing about. In other words, don’t light a match near me.

While we grew up poor, we never knew it. I was always surrounded by books, stories, loving grandparents and relatives who always had plenty of frybread and cigarette smoke to make you feel at home, and we had plenty of cats and other animals we adopted as our own.

I remember when we were young, we plugged newspapers and cardboard into the holes of the floorboards of my mom’s clunky, white Ford Grenada to prevent snow and water from splashing up into our faces. One time, I remember sitting in that Granada in the Buche’s grocery store parking lot bawling my eyes out. Mom had gotten into an argument with the cashier. I didn’t understand at the time but she wasn’t allowed to purchase groceries that day. According the cashier, she had used up all her store credit. So we went hungry. She later told me the cashier made a comment about refusing service to a broke, single mom raising two children from different dads — one white and one Native. Little did she know my blonde-haired, blue-eyed brother had the same dad. He was just pulled from the oven too quickly and didn’t get time to brown up!

Those are the things I remember growing up. There was plenty of tragedy, humor, and rage.

In my teens, I remember my first love: punk rock. Punk rock saved my life. It connected me with young people all over South Dakota who wanted a different world, a better world. We traveled to underground basement shows and talked about radical politics. Most in the scene were poor white kids who grew up in trailer parks on the ride side of the tracks like me. Punk rock brought me to Omaha in 2003. Feeling much like I do today as I did fourteen years ago, I detested war and was outraged like millions across the globe that the US invaded Iraq. After my shift ended at Pizza Hut one night, a close friend and I drove to Omaha to protest the second Iraq War. I was 17. It was the first time I smelled teargas and the first time I tasted pepper spray. It made me think, why is peace is so violent? I was forever changed. I joined the movement and never left. This moment is when my education really began.

Punk rock also brought me to Vermillion and to USD. All my friends had come here to start an activist and punk scene. I can’t remember if I chose to come here to go to school or to become an organizer. Either way, it was cheap and I got some scholarship money. Reading for coursework was perhaps an added benefit. After a while, I was the only one of my peers still attending classes. Nevertheless, I spent six years here finishing my undergraduate degree in history in 2008 and leaving grad school 2010 to take care of my dying mother and returning in 2013 to finish my master’s degree in history.

Later, I would learn I was the only one of my freshmen cohort of eighteen Native students to finish my undergraduate degree at USD. At the time I had graduated high school, Natives had a seventy-five percent dropout rate just from public schools. Why did I stay in school? And why did my peers dropout? There are several reasons. No matter what, if I had stayed out all night for a show or whatever, I always attended my classes. Attendance wasn’t perfect, but you get the picture. I credit GEARUP for my educational successes. Had it not been for that program, I would not be here today. Most of you in the room would not be here today.

My freshmen and sophomore year, I was in the earth sciences, convinced I could save the planet with science. I was fairly good at math and loved learning about our planet. I still love science. Math, not so much. This all changed the semester I took a required US History survey course. The professor, now retired, made several racist comments about Natives in class. Upset, I spoke with him after class. I expressed my concerns. He quickly dismissed me by saying, “I don’t get paid six digits a year to make this shit up!” He turned his back to me and walked away. I got a C in the course and decided I was going to become a historian. I would like to add: as it turned out, I really enjoyed history and my history professors were not all racists.

****

As Native students, we organized to get the American Indian Studies program out of the basement of Dakota Hall — which we did. Imagine that, you’re in the basement of the building that’s named after you. We also attempted to get USD to abolish its racist alma mater song, known as “The Pioneer Spirit,” which celebrates the conquest of “untried frontiers.” It doesn’t matter if you’re Native or non-Native. It’s embarrassing to have your educational achievements tarnished by a song that celebrates the theft of the Black Hills and the conquering and genocide of Indigenous peoples. For those who are going to graduate, at the graduation ceremony it may be your first time hearing the song. So here’s your warning.

It’s important to consider the particular history of this institution and what it chooses to celebrate, remember, and forget. Institutional memory and celebrations speak to a university’s committed values. USD is a land grant institution. After the genocidal conclusion of the 1862 US-Dakota War, USD was awarded land by the federal government. As I mentioned above, my ancestors were targeted for extermination during that war. Weeks after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, he ordered the hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota as punishment for the Dakota Uprising. This is how USD was founded: on stolen Indian land. There was nothing “untried” about these frontiers. These frontiers were inhabited by people. As university campuses around the nation begin to abolish symbols of white supremacy such Confederate flags and buildings named after slave owners, USD needs to seriously consider its commitments not just to Native people but to everyone. Does USD stand for Indigenous genocide? If not, then why does the institution celebrate it? It always concerns me when people confuse reverence with memory. Abolishing a racist song, mascot, statue, etc. doesn’t erase history. Those things are about reverence — appreciation, respect, and honor. We can remember Indigenous genocide without celebrating it. That’s what historians and the unread books we write are for.

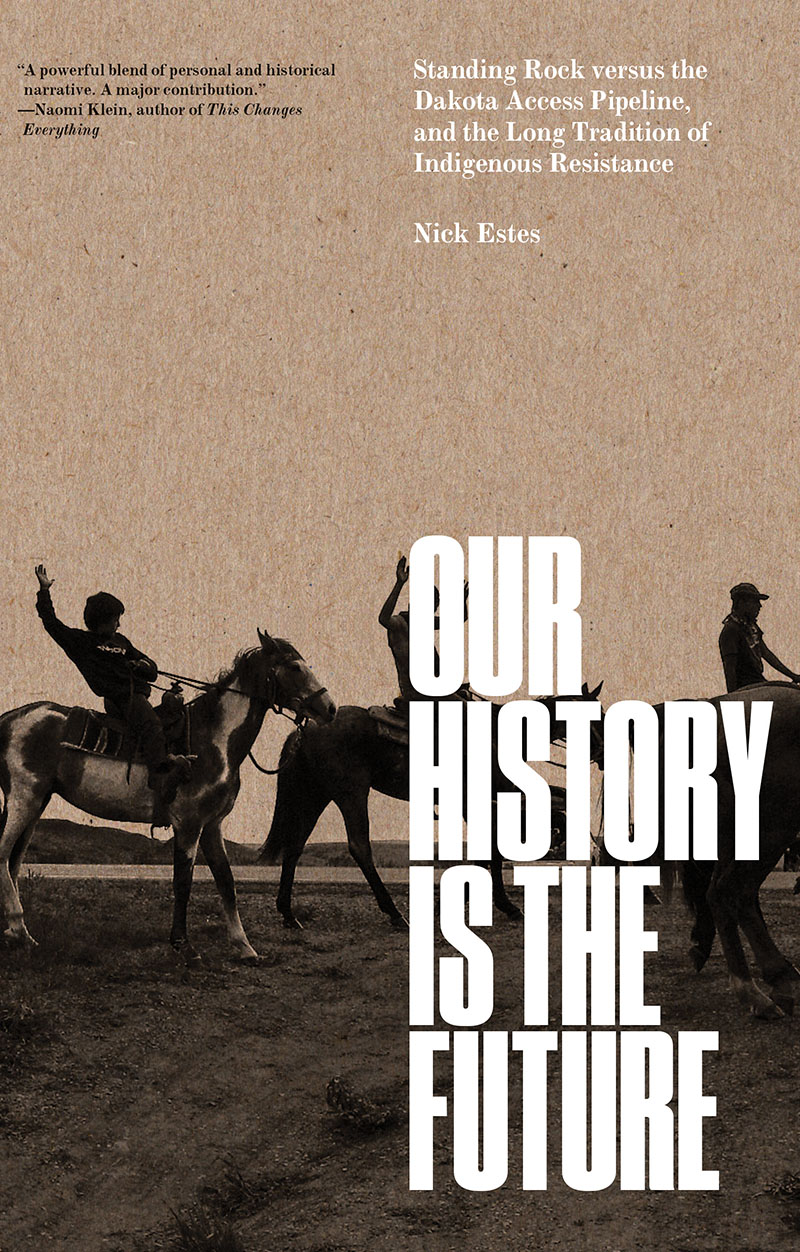

But I would also caution: these are not histories that are safely confined to the past. They are very much alive and well in the present. We only need to look to Standing Rock and the heroic effort by Water Protectors to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. We should be talking about what happened in Standing Rock and why it posed such a threat to the order of things. I’m not sure what the media in South Dakota has been saying, but Standing Rock was about more than stopping a pipeline. I spent some time up there and I want to share some perspectives with you about my experience. It speaks to what a possible more just and peaceful future may look like.

We live in an era where many people in this state, especially it’s elected leadership, view Indigenous sovereignty and treaties as a threat. This view is interesting because it gets at the heart of what Standing Rock was all about. What is widely dubbed the #NoDAPL movement is about upholding the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty and about protecting the water from inevitable contamination. After all, it’s not if the pipeline breaks but when. All pipelines break, no matter how safe or how thick the Chinese-manufactured steel. Most critics will say that treaties are ancient documents with no relevance in the present. There is a document older than the treaties — the US Constitution — that says “treaties are the Supreme Law of the land.” As Lakotas and Dakotas, we may be familiar with all these arguments. And they are all sound arguments.

Opponents of treaties, Indigenous sovereignty, and giving land back to its rightful caretakers are really just afraid we will do to them what they did to us: genocide, removal, confinement to reservations, the destruction of lands and water, etc. That’s a curious assumption. First, there is an implicit acknowledgement of fault, that these lands were not “untried frontiers,” that genocide did take place, and that, indeed, this land is stolen. For this settler society to flourish, they had to take our land and we had to give up who we were. Those are not radical things to say. They are truths that we must be courageous enough to admit to ourselves. Second, refusing to acknowledge that their settler government made treaties with us, they take no responsibility. We must remind them, those treaties are not just Indian treaties, they are your treaties, too. It is your responsibility to uphold them, too. Lastly, how unimaginative! Are we possessed only with the capacity to solve problems with war and violence? That’s a very pessimistic view of humanity.

I read some interviews with the cops who worked the pipeline protests. A fair number of law enforcement and military personnel conceded the larger point that the Oceti Sakowin, the Great Sioux Nation, had a legitimate legal, political, and moral claim to stop the pipeline. One cop told a reporter, “The conversation among those in the camp has changed to treaty lands. That won’t be decided out here, at this level, but they have a very valid argument there. They might be on to something if they pursue that.” That raises an important question. If there are wrongs committed and indeed this land was never ceded the United States, then what authority does a local county sheriff’s office have to weigh in on treaty rights and stolen land? The police should never have been there in the first place. They should never have done what they did to people.

But, I suppose, you need an enemy and someone to blame. Why not blame the Indians? It seems like the narrative portrayed in North Dakota was that angry Indians who hated white people were burning cars and scaring little white children in shopping malls. If we look at Standing Rock, that was simply not the case. In fact, the opposite happened and that what was most terrifying for North Dakota and South Dakota pipeline advocates.

The people who came to defend the land, the water, and treaties — many of them were non-Natives. Some of them were poor white kids I went to high school with who felt completely disempowered and betrayed by their own government. Free education, healthcare, and clean drinking water are more radical demands than spending $30 million in disaster relief money to bring in 76 law enforcement agencies from around the country, homeland security, border patrol, and that National Guard to brutally beat, harass, mock, and degrade people who want to pray with water. For what? A $3.7 billion pipeline that will only create a dozen or so permanent jobs? While we can blame Trump for many things, the Dakota Access pipeline began under Obama.

After the banks crashed the global economy and millions lost their jobs and their homes, the US government initially paid out $700 billion to the banks responsible for crashing the market. Forbes has now estimated that federal bailouts to banks will amount to more $16.8 trillion, with $4.6 trillion already paid out. Many of the banks bankrolling DAPL initially received tens of billions of dollars in federal bailout money. Everyone is still reeling from the effects of the Great Recession. Opioid addiction has skyrocketed among white communities. When I go back to Chamberlain, I see the effects of addiction and how it has devastated that town. But addiction is the symptom of our current economic and political moment. It should not surprise us. Instead of an increase of educational and employment opportunities, we have instead seen the pillaging of the earth for corporations to reap huge profits. That was Obama’s economic recovery plan and that has been accelerated under Trump. Since 2010, ten Keystone XL pipelines have been built and domestic oil production increased by 70 percent. In contrast, if we look at South Dakota’s economy we often think agriculture is the number one wealth producer in this state. In fact, the vast majority of this state’s wealth is not produced by farmers or the oil industry. The vast majority of the wealth in this state is produced by the service industry — the people who work in fast food, retail, and healthcare. This class of people is also the group that shoulders the largest tax burden but they are consistently neglected when we talk about wealth and power in this state. We have drilled our way out of recession at the expense of Indigenous land and poor working people. Poor white people were as much squeezed by the recession and hoodwinked by the bailouts under Bush, Obama, and now Trump as anyone else.

These are not bold alternatives; these are status quo visions. They are cowardly visions. They jeopardize the land and the history it carries, and they jeopardize a livable future. We are experiencing the earth’s six mass extinction event, an event that has been — without out a doubt — linked irreversible catastrophic climate change. It is a system-driven extinction, a system called capitalism. And it must be system-driven solution that cannot be capitalism.

In her poem “i am graffiti,” Anishnabe poet, activist, and scholar Leanne Betasomoke Simpson writes,

we are the singing remnants

left over

after the bomb went off in slow motion

over a century instead of a fractionated second.

We are the singing remnants in the age of the slow bomb that not only targeted people for destruction, but also the planet. As Simpson points out in the title of the poem, we are the “graffiti” this system tries to paint over again and again to erase us. However beautiful we may be, however bold our messages are, and not matter who stands with us, like graffiti we are still considered criminal.

That’s why Standing Rock mattered. The states of North Dakota and South Dakota have always feared poor white people and Natives getting together and taking their destinies into their own hands. At its best moments, that’s what happened at the camps at the confluence of the Cannon Ball and Missouri rivers: everyday Native and non-Native people got together. They decided they were not only against a pipeline, but they also stood for something. The media and the institutions of power have instilled fear into white people that the Indian Problem is out of control and that they will all be kicked off the land if we give the land back. The opposite happened. We invited them into our circles and we stood together.

That’s the fundamental misunderstanding when we talk about racism and colonialism. We are taught racism and colonialism are meant to control Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples. And they do control us. But racism and colonialism are really meant to control white people. That’s a lesson from Standing Rock worth remembering.

Now there is talk of reconciliation. And that deeply concerns me. The word reconcile is problematic. It means that two equal parties come together to reestablish friendly relations. It assumes that there was equal fault on both sides and that hostilities have ceased. Neither of those things are true. Unless we’re talking about land return and the abolition of colonial institutions, reconciliation is deficient and cannot achieve the kind of justice necessary to make Indigenous nations and the planet live again.

But that doesn’t mean we are without hope. Two generations ago, my grandparents fought to protect the Missouri River and their lands against the Army Corps of Engineers. The Pick-Sloan dams would flood over half a million acres of land, most of which was Indigenous land. As a result, thirty percent of the populations of Lower Brule, Crow Creek, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock were removed. Ninety percent of commercial reservation timber and seventy-five percent of wildlife was destroyed. My grandparents could never have imagined that across the world, millions of people would rally and march in major cities to protect our river. And that’s a very beautiful thing.

More so now than just a year prior, people are waking up. Standing Rock will be one of many, many important changes to come. It’s rather ironic when you think about it. Under this president, we feel more free to talk about the past and about a future than just a year ago.

****

We are living in historic times. No matter how alone or afraid we feel, we must remember we have relatives. That has been a major comfort for me. The histories I write and read are, indeed, nightmarish. But these histories are full of our ancestors’ stories. History is not something that if you ignore it long enough it will go away. History is an active element, very much alive in the present. For Indigenous peoples, we take comfort knowing our ancestors are always with us.

That’s why history is important. To know one’s history is to not be held captive by it. For Indigenous peoples, we have no choice but to engage with settler society at all turns. Settler society, however, can choose to engage us or not. Often it chooses not to.

Over the years we have made new relations — it’s what sustained us and what kept us alive as people.

And that’s where I want to leave you all tonight. I want you to think about your relations. When we say, Mitakuye Oyasin, we are all related, we mean everyone and every-thing. To be a good relative to the human and nonhuman world is the ultimate Lakota virtue. It’s something we all should aspire to in our lives. It protects us. And we will protect our relatives. So we can all walk without fear, whether plants, animals, or the most vulnerable of this world. That is the world we have to imagine and demand can exist. It is possible.

With that in mind, I want to leave you with the words of Dakota scholar Ella Deloria. In these dark times, her words have taught me not to fear but to take courage in my relations and my relations to take courage in me. She wrote, “I am not afraid; I have relatives.” Let’s take courage in this affirmation. Repeat after me:

“I am not afraid; I have relatives.”

“I am not afraid; I have relatives.”

“I am not afraid; I have relatives.”

“I am not afraid; I have relatives.”

Now look around you. You are surrounded by relatives. This is what I love to return home to, a room full of fearless relatives.

Hecetu Welo!